The Living Heart Project.

’Rebooting’ donor hearts with HOPE - hypothermic oxygenated perfusion.

The first major innovation in heart transplant in over 60 years.

A new way to transport and protect donor hearts

CCRG has perfected the use of a novel hypothermic oxygenated perfusion (HOPE) device that has revolutionised the practice of heart transplantation internationally.

The device allows donor hearts to rest and be rejuvenated before transplantation, perfused with a medical “Gatorade” rich in oxygen and nutrients. HOPE also allows donor heart to remain ‘ex vivo’ outside the body for >3 times longer and cover distances never thought possible.

Heart failure is a growing health epidemic globally, the world’s biggest killer. Once developed, is irreversible and fatal.

Heart transplant (HTx) is the only effective treatment for end-stage heart disease, yet organ shortage is the greatest challenge facing the transplant field today. Consequently, only a small number of patients with end-stage heart disease are given the opportunity of a transplant.

Until recently, donor hearts were still placed in an ice slush to be transported between donor and recipient. This method provides limited transport time before the heart is at risk of poor function in the recipient, hence many donor hearts in Australia and New Zealand cannot be transplanted because the transport time is excessively long. Poor function of the donor heart once transplanted into the recipient is the major driver of morbidity and mortality after HTx.

CCRG has demonstrated that with HOPE donor hearts can remain outside the body for over 13 hours, more that three times longer than when stored in ice.

The Living Heart Project represents the first major innovation in the field of heart transplantation in over 60 years.

CCRG developed the most advanced, clinically relevant model to examine the use of HOPE and shepherd the use of this technology into clinical practice internationally.

Using machine perfusion, every donor heart in Australia and Ne Zealand can now be transported to a transplant centre in either country.

This has increased the volume of donor hearts available each year by approx. 20-25%.

Meet Alex, 24-year-old recipient of a donor heart transported with HOPE

In the cardiac ward of a Perth hospital waiting for a donor heart, adrenaline fed through her veins from a drip was the only thing keeping her alive as her failing heart struggled to pump blood.

“I was very grey, I was so pale that I was see-through,” Ms Moroianu says. “My heart was so enlarged, it would shake my body with every pump.”

Although doctors did not know why their young patient’s heart was failing, they knew she would not survive long without a transplant. She was placed on the transplant waiting list, but in Western Australia, hearts are donated only about once every four or five days, and not all donated hearts are suitable for every individual. The east coast was too far away for a donor heart to be transported and survive.

Deprived of oxygen, the precious organs deteriorate fast – within four to five hours – and it’s a race against time. Three out of four donor hearts nationally are currently discarded.

-

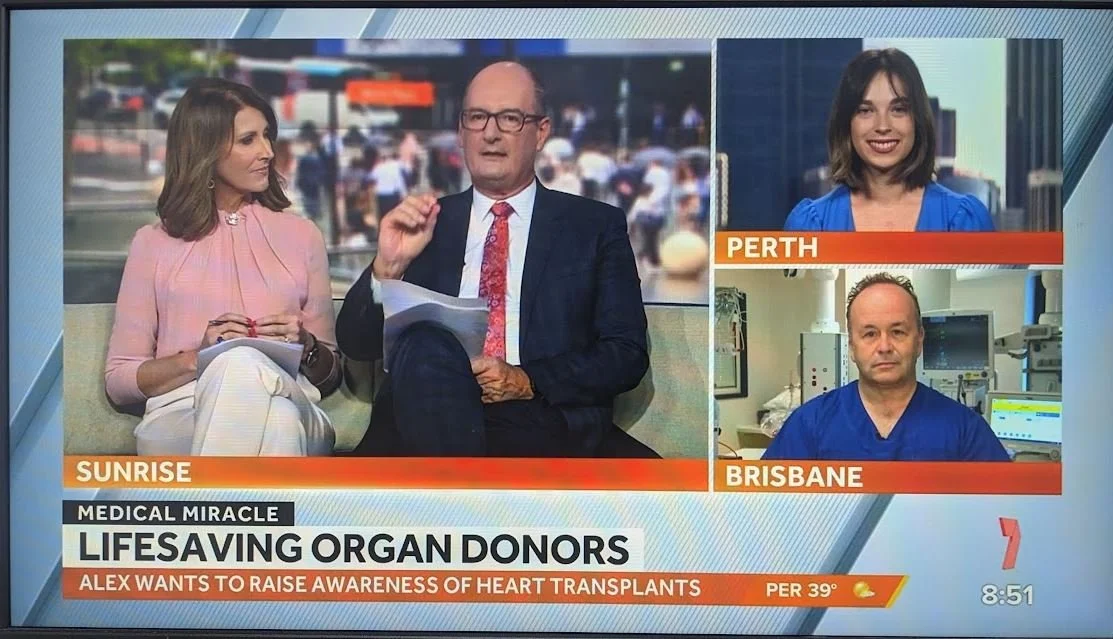

National coverage for The Living Heart Project

Heart transplant recipient Alex Moroianu spoke to Channel 7’s Sunrise to raise awareness for heart transplants

-

Meet donor heart recipient Alex Moroianu

Alex is one of 30+ Australian who have benefited from a new medtech device with practices developed by the Critical Care Research Group, St Vincent’s Hospital and Alfred Health

-

![Louise CCRG]()

The Living Heart Project is generously funded by The Common Good, an iniative of The Prince Charles Hospital

-

![]()

The gift of life... straight from the heart

In the cardiac ward of a Perth hospital waiting for a donor heart, adrenaline being fed through her veins was the only thing keeping Alexandra Moroianu alive. Until a chance meeting with CCRG’s Professor David McGiffin.

-

![]()

Australian device plays key role in historic heart transplant

Australian scientists have been praised by the team behind the historic pig-to-human HTx.

-

![Afternoons-with-Sofie-Formica]()

How Brisbane assisted world first surgery

A team of researchers based in Brisbane played a role in a world first surgery, when a pig’s heart was successfully transplanted into a man in the US.

Select Publications

Bin, L., McGiffin, D., Nguyen, T., Wang, L., Sun, Y., Ye, L., Han, M., Sheng, C., Lee, T., Aguilar, M., Peleg, A., Qu, Y.

Colombo, S. M., Karnik, V., Rickards, L., See Hoe, L., Wildi, K., Passmore, M., Suen, J., McGriffin, D., Fraser, J., Li Bassi, G.

Shaarbaf Ebrahimi, B., Khwaounjoo, P., Chan, H., Argus, F., Ma, X., Nash, M. P., Doi, A., Dagan, M., Kaye, D. M., Joseph, T., McGiffin, D., Tawhai, M. H.

Obonyo, N., Lu, L., Nadeem, Z., Hosseinzadeh, Z., Rachakonda, R., White, N., Sela, D., Tunbridge, M., Sim, B., See Hoe, L., Sivakumaran, Y., Li Bassi, G., Fanning, J., Tung, J., Suen, J., Fraser, J.

See Hoe, L.E., Bouquet, M., Bartnikowski, N., Wells, M.A., Devaux, J., Hyslop, K., Passmore, M.R., Wilson, E.S., Reid, J.D., O'Neill, H., Shuker, T., Obonyo, N.G., Sato, K., Heinsar, S., Wildi, K., Ainola, C., Abbate, G., Peart, J.N., Wendt, L., Engkilde-Pedersen, S., Parker, S.E., Lu, L., White, N., Molenaar, P., Li Bassi, G., Haqqani, H., McGiffin, D.C., Suen, J.Y., Fraser, J.F.

Celik A, Lindstedt S, McGiffin DC, Suen JY, Fraser JF, Del Nido PJ, Emani SM, McCully JD.

Nonaka, H., Yu, L., Obonyo Nchafatso, G., Suen, J., McGiffin, D., Fanning, J., Fraser, J.

Chan, C., Passmore, M., Tronstad, O., Seale, H., Bouquet, M., White, N., Teruya, J., Hogan, A., Platts, D., Chan, W., Dashwood, A., McGiffin, D., Maiorana, A., Hayward, C., Simmonds, M., Tansley, G., Suen, J., Fraser, J., Meyns, B., Fresiello, L., Jacobs, S.

Gandini, L., de Veer, S., Chan, C., Passmore, M., Liu, K., Lundon, B., Rachakonda, R., White, N., Rhodes, M., Shanahan, E., Yap, K., See Hoe, L., Semenzin, C., Li Bassi, G., Fraser, J., Craik, D., Suen, J.

Obonyo, N. G., Sela, D. P., White, N., Tunbridge, M., Sim, B., Rachakonda, R. H., See Hoe, L. E., Li Bassi, G., Fanning, J. P., Tung, J.-P., Suen, J. Y., & Fraser, J. F.

Haymet, A. B., Lau, C., Cho, C., O’Loughlin, S., Pinto, N. V., McGiffin, D. C., Vallely, M. P., Suen, J. Y., Fraser, J. F.

Karnik, V., Colombo, S. M., Rickards, L., Heinsar, S., See Hoe, L. E., Wildi, K., Passmore, M. R., Bouquet, M., Sato, K., Ainola, C., Bartnikowski, N., Wilson, E. S., Hyslop, K., Skeggs, K., Obonyo, N. G., McDonald, C., Livingstone, S., Abbate, G., Haymet, A., Jung, J.-S., Sato, N., James, L., Lloyd, B., White, N., Palmieri, C., Buckland, M., Suen, J. Y., McGiffin, D. C., Fraser, J. F., Li Bassi, G.

Nchafatso G. Obonyo, Sainath Raman, Jacky Y. Suen, Kate M. Peters, Minh-Duy Phan, Margaret R. Passmore, Mahe Bouquet, Emily S. Wilson, Kieran Hyslop, Chiara Palmieri, Nicole White, Kei Sato, Samia M. Farah, Lucia Gandini, Keibun Liu, Gabriele Fior, Silver Heinsar, Shinichi Ijuin, Sun Kyun Ro, Gabriella Abbate, Carmen Ainola, Noriko Sato, Brooke Lundon, Sofia Portatadino, Reema H. Rachakonda, Bailey Schneider, Amanda Harley, Louise E. See Hoe, Mark A. Schembri, Gianluigi Li Bassi & John F. Fraser.

Obonyo NG, Dhanapathy V, White N, Sela DP, Rachakonda RH, Tunbridge M, Sim B, Teo D, Nadeem Z, See Hoe LE, Bassi GL, Fanning JP, Tung JP, Suen JY, Fraser JF

Sato K, See Hoe L, Chan J, Obonyo NG, Wildi K, Heinsar S, Colombo SM, Ainola C, Abbate G, Sato N, Passmore MR, Bouquet M, Wilson ES, Hyslop K, Livingstone S, Haymet A, Jung JS, Skeggs K, Palmieri C, White N, Platts D, Suen JY, McGiffin DC, Bassi GL, Fraser JF

Chan CHH, Passmore MR, Tronstad O, Seale H, Bouquet M, White N, Teruya J, Hogan A, Platts D, Chan W, Dashwood AM, McGiffin DC, Maiorana AJ, Hayward CS, Simmonds MJ, Tansley GD, Suen JY, Fraser JF, Meyns B, Fresiello L, Jacobs S.

Obonyo NG, Sela DP, Raman S, Rachakonda R, Schneider B, Hoe LES, Fanning JP, Bassi GL, Maitland K, Suen JY, Fraser JF.

David C. McGiffin, Christina E. Kure, Peter S. Macdonald, Paul C. Jansz, Sam Emmanuel, Silvana F. Marasco, Atsuo Doi, Chris Merry, Robert Larbalestier, Amit Shah, Agneta Geldenhuys, Amul K. Sibal, Cara A. Wasywich, Jacob Mathew, Eldho Paul, Caitlin Cheshire, Angeline Leet, James L. Hare, Sandra Graham, John F. Fraser, David M. Kaye

Emmanuel S, Muthiah K, Tardo D, MacDonald P, Hayward C, McGiffin D, Kaye D, Fraser J, Jansz P

Amanda S. Cavalcanti, Raquel Sanchez Diaz, Eleonore C.L. Bolle, Nicole Bartnikowski, John F. Fraser, David McGiffin, Flavia Medeiros Savi, Abbas Shafiee, Tim R. Dargaville, Shaun D. Gregory.

Wells, M. A., See Hoe, L. E., Heather, L. C., Molenaar, P., Suen, J. Y., Peart, J., McGiffin, D., & Fraser, J. F. (2021).

See Hoe, L.E., Wildi, K., Obonyo, N.G. et al. A clinically relevant sheep model of orthotopic heart transplantation 24 h after donor brainstem death. ICMx 9, 60 (2021).

Wells, M. A., et al. (2021). "Compromised right ventricular contractility in an ovine model of heart transplantation following 24 h donor brain stem death." Pharmacological Research 169: 12.

Wallinder, A., et al. (2017). "ECMO as a bridge to non-transplant cardiac surgery." Journal of Cardiac Surgery 32(8): 514-521.

“For some time, we have been following the Critical Care Research Group’s impressive work and the subsequent clinical trials with great interest. Their preclinical results encouraged our use of the same system here and gave us confidence to move ahead with a transplant into a human.”

Dr Bartley Griffith, MD

University of Maryland School of Medicine

Muhammad M. Mohiuddin, MD, who worked alongside Dr Griffith said: “Without HEVP technology this transplant would never have happened.”

More Critical Care Research Group Projects

-

![ICU of the Future]()

ICU of the Future

A better ICU experience so patients THRIVE, not just survive

-

![Biomedical Engineering

The Innovative Cardiovascular Engineering and Technology Laboratory (ICETLab) facilitates the translation of innovative cardiovascular technologies from idea to clinical implementation, whilst also investigating the clinical ch]()

ICETLab

Taking novel cardiovascular technologies from idea to implementation

-

![A collage of numerous virtual meeting participants with various national flags visible behind or around them, centered around a logo for the COVID-19 Critical Care Consortium.]()

COVID-19 Critical Care Consortium

Creating the world’s largest database on COVID-19 ICU patient data

-

![Research Translation

Our Scientific and Translational Research Laboratory (STARLab) focuses on heart, lungs and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) research. In particular, projects involve heart transplant (HTx), lung transplant, heart failur]()

STARLab

Imperative research related to the heart, lungs and ECMO

-

![Two medical professionals in surgical attire, including masks, gloves, and caps, are working in an operating room. They are attending to a patient on an operating table, which is covered with blue surgical drapes. Medical equipment, monitors, and supplies surround them.]()

PRIMELab

The largest preclinical ICU in the southern hemisphere testing the efficacy of ground breaking surgical interventions